“Birds can nest in winter?”

This is a frequent question I receive when I mention that Red Crossbills are currently nesting in several locations in the Adirondacks — including Newcomb and Minerva. Red Crossbills (Loxia curvirostra) and White-winged Crossbills (Loxia leucoptera) are finches that can nest at any time of year, but they most frequently nest during winter in the Adirondacks. Crossbills feed their young conifer seeds, so they can nest even in the depths of winter if the cone crop is large enough, which is the case this year.

Canada Jays begin nesting toward the end of winter, usually in late February or early March, and their young fledge in late April. With nesting out of the way in early spring, this allows the year-round Canada Jay to spend late spring and summer caching enough food to make it through the next winter.

Great Horned Owls nest in winter also, usually during February. Young are born after a month of incubation. The owlets remain with their parents for a long time compared to other species – until early fall. By nesting in winter, Great Horned Owls give their young enough time to learn how to survive on their own before the following winter.

It’s all about food

Birds are warm blooded animals and much of their behavior, including nesting, migration, and other movements, is all about finding enough to eat. A common misconception is that cold weather is responsible for some bird species migrating. It’s not the cold temperatures, but the changing food sources as a result of those temperatures (especially the effects on insects), that are the impetus for some birds’ movements. Many waterfowl species will stay north as long as they have open water for foraging, and with our rapidly warming climate, the birds are staying longer and longer as the lakes ice over later and later each year.

Interesting Red Crossbill facts

As their name implies, Red Crossbills have bills that are crossed. Roughly half of Red Crossbills have upper mandibles that cross to the right, and half to the left. This unique physical characteristic allows the birds to open cone scales so their tongue can reach the seeds. If a cone is closed, the crossbills will bite off the cone and hold it with their toes as they open it. If the cone is already opened, the birds will use their bills and feet to hang, parrot-like, in all kinds of positions in order to access the seeds.

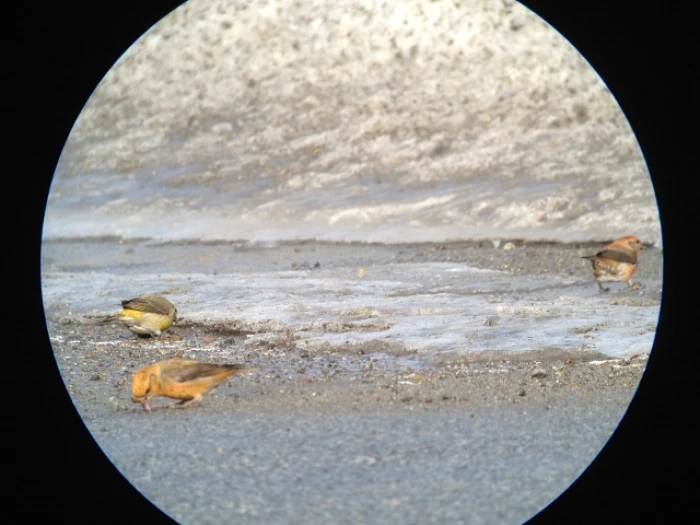

Male Red Crossbills are red (sometimes orange) and females are greenish-yellow. Both have dark wings and tails.

During nesting, the female Red Crossbill does all of the incubation, and then all of the brooding of nestlings. Red Crossbills are monogamous and the male feeds the female during courtship and incubation, and he feeds the young after they hatch. By the time the young are 5-days-old, both parents feed them. By the end of winter or early spring, it is wonderful to see the heavily striped Red Crossbill fledglings!

The Red Crossbill is considered a mostly western U.S. species as you can see by its range map.

Red Crossbills are “nomadic” birds. They move from place to place based upon the variable nature of cone production, sometimes all the way across the continent. Unlike most migratory birds that nest in one location, winter in another, and then return to the same place to nest, Red Crossbills only show up to breed and forage based on the size of the cone crop.

Both Red and White-winged Crossbills spend a lot of time “gritting” - taking sand and salt from the roadways. Unfortunately, they are often killed by vehicles since they don’t fly out of the way in time. If a Red Crossbill’s upper mandible points to the right, the bird will turn its head to the left to grit, and if the bird’s upper mandible points to the left, it will turn its head to the right to grit.

Whenever I’ve observed Red Crossbills drinking, they are always positioned upside down!

Scientists believe there are at least 10 different Red Crossbill sub-species based on the differences in their calls and songs, and differently shaped bills. Red Crossbills specialize on particular coniferous trees for feeding – some preferring various spruces, pines, or hemlock, etc. Their bills are the perfect size for the particular coniferous tree cones on which they feed. The calls have allowed the scientists at the Cornell Lab of Ornithology to separate Red Crossbills into different “Types,” which are likely different species. I often record calling birds and send the recordings to Cornell for identification. Most of the birds in Newcomb and Minerva are Type 2 birds which have a loud call note. The Red Crossbills recorded in Long Lake are Type 10 birds, which have a softer call note. Multiple “Types” of Red Crossbills will often nest near each other, but they do not inter-breed. If scientists decide to separate, or “split,” Red Crossbills into multiple species, it will be tricky for birders to distinguish them since they all look alike!

With an excellent cone crop on most coniferous trees, this is a terrific winter for observing beautiful Red Crossbills. In Newcomb and Minerva, watch for this species along Route 28N from the scenic overlook in Newcomb to a mile or two east of the Boreas River in Minerva. Listen for their loud, “jip, jip, jip” calls. The best time to look for Red Crossbills is early in the morning just after a new snowfall when the plows have recently salted and sanded the highways. The crossbills will be gritting in the road.

It always seems like such a gift to have Red Crossbills singing and nesting during the heart of the Adirondack winter!

In addition to great roadside birding along Route 28N, there are many trails for cross-country skiing and snowshoeing in the area. And after your outing, there are wonderful places to dine and spend the night.