After the 2013 film “12 Years a Slave,” which won the Academy Award for that year’s best picture, most people are familiar with the story of Solomon Northrup, a free black man who was kidnapped and sold into slavery in 1841.

It’s not as widely known, however, that Solomon was a son of the Adirondacks. He was born in the tiny town of Minerva to a father who was a freed slave and a mother who was a free woman of color.

It’s crazy to think that a remote place like Minerva, so peaceful and so wild, could be the birthplace of a person who had such a huge impact on a nation.

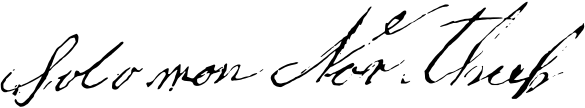

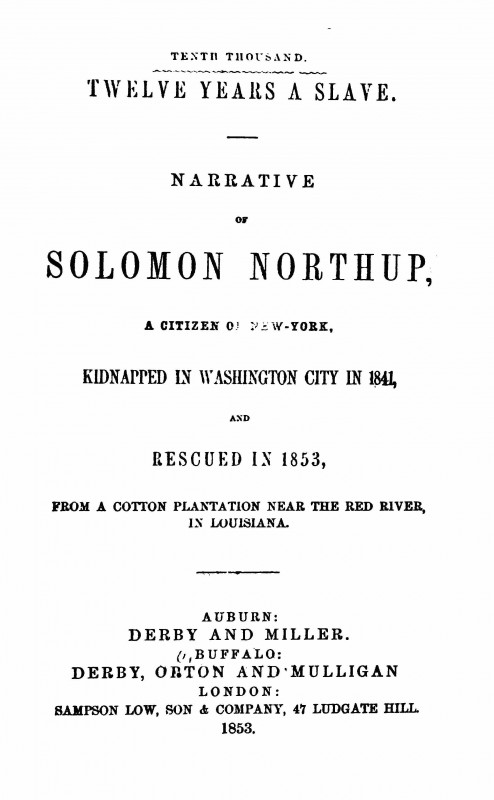

Solomon was saved from the bonds of slavery after 12 years of toiling in the south. The same year he was freed, 1853, he released a book chronicling his troubles, called “12 Years a Slave.”

That book went on to sell 30,000 copies and was read widely, showing America at the time of the institution of slavery in a brutally honest light. Most accounts of slavery at that time were either too rosy or unrealistically negative, but Solomon’s narrative made it clear that while there was plenty of horrors and brutality, it wasn’t all bad, that there were moments of levity and human kindness even in captivity.

If Harriet Beecher Stowe’s “Uncle Tom’s Cabin” was the first book to open up the country’s eyes to slavery, “12 Years a Slave” was the confirmation that what she wrote was true. Solomon dedicated his book to Stowe: “TO HARRIET BEECHER STOWE: WHOSE NAME, THROUGHOUT THE WORLD, IS IDENTIFIED WITH THE GREAT REFORM: THIS NARRATIVE, AFFORDING ANOTHER Key to Uncle Tom's Cabin, IS RESPECTFULLY DEDICATED.”

Those books, in part, laid the groundwork for the American Civil War, which lead to the end of slavery.

Minerva in the early 1800s

Solomon mentions Minerva briefly in his book, as he discusses his heritage. His father, Mintus Northrup, came from a long line of slaves in Rhode Island, and he moved to Rensselaer County with his owner. When his owner died, he used his will to free Mintus.

“Sometime after my father’s liberation, he removed to the town of Minerva, Essex County, N.Y., where I was born, in the month of July, 1808. How long he remained in the latter place I have not the means of definitely ascertaining.”

At the time, Minerva wasn’t even formed yet. The town was part of the town of Schroon until 1817. Another portion of it was considered part of the town of Newcomb until 1828, and in 1870, Minerva took more land from the town of Schroon. Today, the town is 162 square miles. Only 137 people were listed as residents of Minerva on the 1810 census. The town was built up around lumbering operations, then mining. Today, that number has grown to 809, as of 2010.

Solomon’s kidnapping

Sometime after Solomon's birth, his parents moved him and his older brother Robert with them to the southern foothills of the Adirondacks. They lived in various places around the Glens Falls/Fort Edward area, Mintus working on different farms along the way. Mintus died when Solomon was 21, and the boys' mother died while Solomon was in captivity.

Mintus took the name Northrup from the family of his owner, and in his life as a freed slave he spoke warmly about the family. He was, however, very aware of the effects of slavery on himself and his race in general. Solomon writes in his memoir that his father made sure to teach them a strong sense of morality, which helped Solomon survive and keep his humanity through years of beatings and mistreatment as a captive slave.

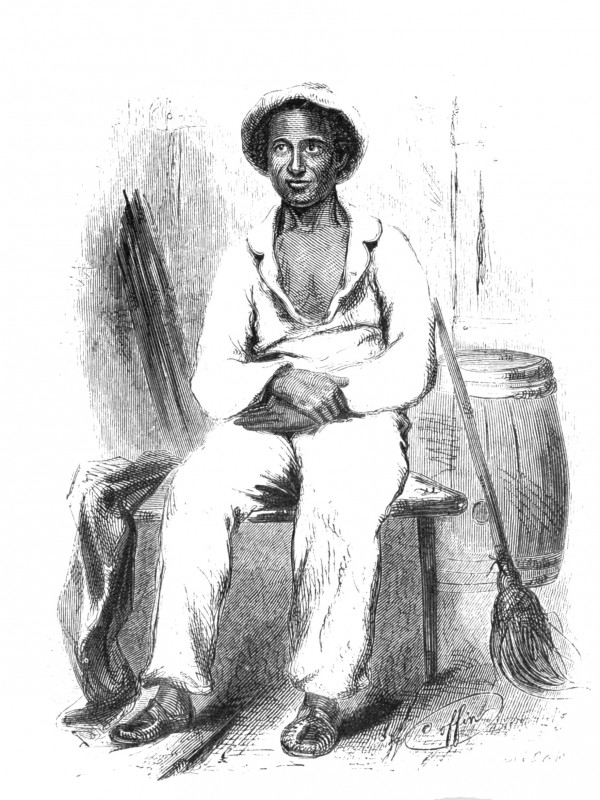

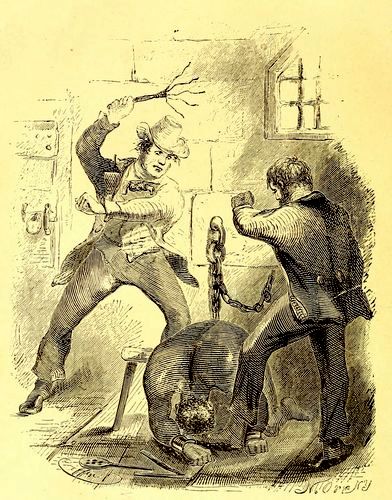

Solomon married at 21 and moved around the Fort Edward area, ending up in Saratoga working in hotels and playing violin at parties. One day in 1841, he was looking for work when he met two white men who had heard what a great violinist he was, and they asked him to come to New York City with them to help with a show advertising for the circus. It sounded like easy, quick money, so he went along, and once they were there, they enticed him to follow them to Washington D.C. It was there that he was seemingly drugged, and he woke up in a hidden slave cell on Pennsylvania Avenue.

He was sold into slavery, living first with a benevolent plantation owner who treated him well, then dealing with two who were merciless. It wasn’t until a Canadian carpenter named Samuel Bass came to work on the same plantation that Solomon found a sympathetic ear. Bass wrote letters to Solomon’s family and friends, one of whom came south to save him at long last.

The aftermath

Within a year, Solomon had released his book, and he started venturing out on speaking tours to promote it and to share his story with everyone who would listen. He also got involved in helping with the Underground Railroad, which ran through the North Country and up to Canada.

Not much is known about Solomon’s life after that. He is said to have died in 1863, the same year as the Emancipation Proclamation, but no one knows where, when or how he died. Of course, theories abound: Perhaps he got kidnapped again. Perhaps his work with the Underground Railroad got dangerous and he was killed. Perhaps he just floated off and started another life, and he died where no one knew him. No historian has yet found evidence to give strong enough support to any one theory yet, though some continue to search.

As a sad footnote, both the man that sold Solomon into slavery and the two men who lured him into the trap that made such a thing possible were brought to court as some attempt to find justice for Solomon. Unfortunately, that never happened. The slave trader got off easily due to the fact that Solomon, as a black man, could not testify against him under Washington law at the time.

He was able to testify against the other two in New York court, but those charges were dropped after several years of appeals.

But despite not being able to get tangible justice in his life, Solomon’s story left quite a legacy. It educated Americans about the truth of slavery, and it was no doubt one of the catalysts that lead to the chain of national events that lead to slaves finally being freed.